Hadeel Assad is a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating all types of cancers. But she struggles to convince her own mother to get checked for breast cancer regularly.

“In my culture, cancer has been a taboo,” says Assad, whose family has roots in the Middle East. “People don’t even like to mention the word, let alone do their screening mammograms.”

Assad, a native of Jordan who graduated from the University of Jordan School of Medicine before coming to the United States for her residency and fellowships, says that can add complexity to diagnosis and treatment.

But that hesitation isn’t unique to her Arab-American community. Across many cultures, stigma, mistrust, and negative past experiences shape how people approach cancer care, and sometimes — whether they get it at all. That’s where culturally competent health care comes in.

Culture is the set of values, beliefs, traditions, and behaviors that unite a group of people. It can be based on factors such as race, ethnicity, language, environment, and more. Culture shapes our everyday lives, including the health care we require and receive.

Culturally competent health care is about understanding where you come from and tailoring care plans to your needs and values. This helps make the most out of your treatment.

What Is a Culturally Competent Health Care Team?

A culturally competent health care team is a group of doctors offering medical services to fit your needs. This kind of health care team understands how cultural differences can affect care. They strive to learn more and use this knowledge to inform their services.

A health care team that’s culturally competent also respects the diversity of cultural, religious, and social backgrounds and includes them in your care.

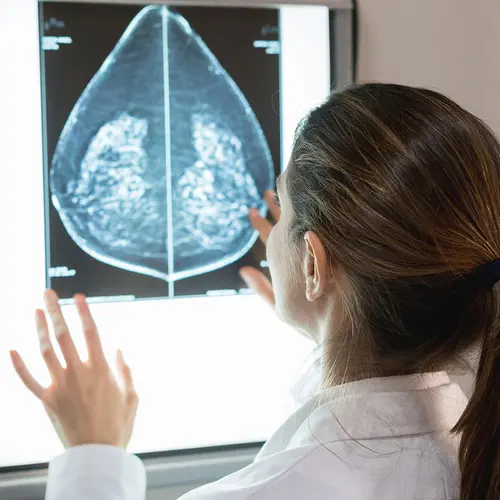

“It goes beyond just avoiding bias," says Assad, who also co-leads the breast cancer multidisciplinary team at Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit. “It means listening to patients’ values, adapting your method of communication, and tailoring your care plan in ways that are both medically sound and meet patients’ values and preferences.”

While cultural competence used to focus mainly on racial and ethnic groups, today, it also includes people with disabilities and those belonging to gender and sexual minorities, different social and economic backgrounds, and other minority communities.

Cultural competence is about one thing — getting the best care for you, whoever you are.

Why cultural competency matters

You may feel uneasy in hospitals or clinics because of past prejudice or unmet cultural needs. This discomfort can stop you from getting the health care you need. People without a regular doctor or health care provider are less likely to get preventive services or get diagnosed and treated for ongoing health conditions, including breast cancer. Research shows that people in minority communities are less likely to have a regular source of health care compared to White people.

When Assad was a medical student, she passed out pamphlets showing how to do a breast self-exam.

“Folks would just give it back to me because they were embarrassed to carry a picture of a breast,” she says.

That embarrassment could mean fewer checkups and later diagnoses. When you have hormone receptor-positive (HR+), HER2-negative breast cancer, treatment can be complex. It often involves high-stakes decisions that may include options such as surgery, chemotherapy, breast reconstruction, and genetic testing.

“These decisions aren’t made in a vacuum,” Assad says. “Patients interpret the risks and benefits through their cultural lens.”

When health care providers recognize your cultural background, it helps build trust and satisfaction and ends differences in care. Plus, treatment plans only work if you trust and follow them.

What a Culturally Competent Breast Cancer Care Team Looks Like

A culturally competent breast cancer care team understands your unique health concerns and the biases affecting your community. Not only that, but they take steps to address them. This could mean hiring staff members of minority communities and training staff in cultural awareness, knowledge, and skills.

Signs of a culturally competent health care team

So what does cultural competency look like in practice? Here are some signs your health care team understands your values and meets your needs.

Language. If English isn’t your first language, your doctor should offer interpreters and translated materials. Health care professionals are required to provide an interpreter for people who need it. This may include people who don’t understand English well (or at all) or who use a different language, such as sign language.

Religion and spirituality. Some hospitals offer prayer rooms and access to spiritual leaders of different faiths. They should respect religious beliefs, especially when it comes to dietary choices, modesty, and same-gender providers during breast exams, as well as culturally appropriate end-of-life care. For example, hospitals should offer kosher or halal meals for people who need them. Modesty gowns — as opposed to the typical hospital gowns — should also be an option.

Sexual and gender identity. Your doctor should use the correct terms that reflect your gender and sexual orientation. And when it comes to breast cancer, they should be aware of factors such as the long-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on cancer risk and treatment. Your doctor should also understand the most relevant screening guidelines if you’re transgender or gender nonconforming.

Race and ethnicity. Research shows that some racial and ethnic minorities distrust health care providers or feel unsafe due to racism or a lack of culturally appropriate care. Community-led initiatives, cultural competency training, and health care workers who reflect your cultural background encourage more people to get care.

Disability. Studies show that people with disabilities often face health disparities, partly because health care providers lack cultural competence. Your doctor should listen to your preferences, needs, and goals instead of making assumptions. They should also use proper language. While many people in the disabled community prefer person-first terms (“person with a disability” rather than “disabled person”), others prefer identity-first language (“autistic person” rather than “a person with autism”). Because language is always evolving, health care providers should make an effort to meet the needs of disabled people and use labels and terms they’d prefer. Medical education should better prepare doctors to work with people with different disabilities.

How to examine cultural competency in breast cancer care

After narrowing down a list of possible doctors, start your research. Find out where they were educated and trained, their years of experience, and any board certifications. If they have a website, check it out to see if it’s diverse. Does the website offer information in languages besides English? Read reviews from people in their care and any articles the doctor has written.

Call the doctor’s office and ask if they offer pre-appointment consultations, either in person or virtually, to discuss becoming a patient. Think about your interactions with the doctor and medical staff. Did they take your concerns seriously? Were they friendly? Did they listen and offer to follow up?

Also, pay attention to whether you saw diverse staff members in the office, from receptionists to doctors.

How to Build a Culturally Competent Breast Cancer Team

Building a culturally competent breast cancer care team involves asking questions, getting the support of loved ones, and finding resources that align with your values.

Connect with local or national breast cancer support groups and cultural health nonprofits that cater to your specific cultural background. They can refer you to hospitals, clinics, and providers that are more sensitive to your needs. Reputable social media and other online tools and communities can also help you find trusted doctors and hospitals.

Ask your hospital if they offer patient navigators. These trained staff members help bridge the gap between cultural and medical resources. Also, remember, you can always get a second opinion.

“A second opinion should be the norm and not an exception, especially if you are feeling that your values are not being respected,” Assad says. “You seek another provider or a cancer center, and that can be very empowering.”

Finally, an important person on your breast cancer care team is a friend or family member. They can help ensure that your values are voiced and understood, especially if you’re unsure about advocating for yourself.

Advocating for Competent Care When You Have Breast Cancer

When you visit your doctor, it can be hard to speak up. You may feel hesitant to ask questions or challenge a doctor’s knowledge and expertise. But it’s critical to stand up for yourself, especially when living with a health condition such as breast cancer.

Before your next appointment, tell the scheduling staff what you want to discuss with your doctor so they can make room for extra time if needed. Then, make a list of questions you’d like to ask related to cultural values. This will help keep your appointment organized and focused. Be sure to ask specific, detailed questions.

“Some of my patients, for example, want to fast during Ramadan, and they’re on chemotherapy. So I talk to them about pros and cons and help them make a decision that best suits them,” Assad says.

Keep in mind: Every doctor won’t be the right fit. If you feel rushed, unheard, or unable to ask questions, it may be time to look for a different doctor.

“Breast cancer treatment is not one-size-fits-all, and patients are never difficult for wanting care that respects who they are,” Assad says. “Cultural respect is part of quality care — It’s not an extra. I often remind my patients: Advocating for yourself improves your care. Providers want to know what matters most to you. So, let them know.”